A few months ago, I turned pro.

By “turned pro,” I mean that I got my novel picked up by one of the major publishing houses in a three-book deal.

I don’t want to overstate what that means. It’s the first step on a long road, and future sales and the conditions of the marketplace may consign me to the remainder rack quicker than you can say “Myke who?”

But it is, for me (and I suspect for most aspiring writers) the main line I sought to cross making the majors, getting picked for the starting lineup.

Put me in coach, I’m ready to play.

Like most of the folks reading this, I was serious and committed, pushing hard for years (all my life dreaming about it, fifteen years seriously pursuing it) with little movement. When I was on the other side of that pane, trying desperately to figure a way in, I grasped at anything I could, looking for the magic formula.

There isn’t one, of course, and everyone told me that, but I never stopped looking.

Now, having reached that major milestone (with so much further to go), I sit and consider what it was that finally put me over the top. Because the truth is that something clicked in the winter of 2008. I sat in Camp Liberty, Baghdad, watching my beloved Coast Guards march past Obama’s inaugural podium on the big screen, and felt it click.

I bitched and whined to anyone who would listen about how unfair life was, about how I just wanted a chance to get my work before an audience, but I knew in my bones that I’d crossed some line. Somehow, going forward, things would be different.

I’ve thought a lot about that time, that shift, and I think I’ve finally put my finger on what changed. The near audible click I heard was my experience in the US military surfacing, breaking the thin skin of ice it had been gathering against for so long. The guy who landed back in the states was different from the one who left. He could sell a book.

We’re all different. We all come at our goals from different angles. I can’t promise that what’s worked for me will work for anyone else. But before I went pro, I wanted to hear what worked for others. I offer this in that same spirit. So, I’ll give you the BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front) as we say in the service: You want to be successful in writing and in life?

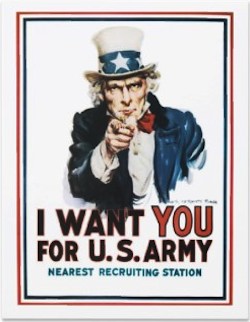

Run, do not walk, to your nearest recruiting station and join up.

I’m not kidding.

Let’s put aside the practical benefits that seem tailor made for the full time writer. Forget the fact that I get full coverage health insurance for $50 a month. Never mind the fact that I get discounts on everything from housing to travel to food to buying cars and cell phone plans. Pay no attention to commissary and gym privileges on any base in the country.

My experience in the military (as a contractor, paramilitary civilian and a uniformed officer) facilitated my writing in three important ways: It taught me the value of misery, it made me focus on quantifiable results, and it made me hungry for challenges, the more seemingly impossible, the better.

Are you sitting comfortably? That might be your problem.

Steven Pressfield is an incredibly successful author. His novel The Legend of Bagger Vance became the film of the same name, and his novel Gates of Fire is widely thought to be the definitive work of historical fiction on the Battle of Thermopylae. Pressfield also wrote The War of Art, which is the only self-help I’ve ever read worth the paper it was printed on.

In The War of Art, Pressfield talks about his experience as a US Marine and how it helped him succeed as a writer. The greatest thing he learned in the Corps? How to be miserable.

“Marines derive a perverse satisfaction from having colder chow, crappier equipment, and higher casualty rates than any outfit of dogfaces, swab jockeys or flyboys . . . The artist must be like that Marine . . . He has to take pride in being more miserable than any soldier or swabbie or jet jockey. Because this is war, baby. And war is hell.”

The human condition is to seek comfort. We want to be well fed and warm. We want to be approved of and loved. We want things to be easy. When something is rough on you, the natural instinct is to avoid it.

You put your hand on a hot stove, you pull it away. Who volunteers to alternately shiver and boil in a godforsaken desert, showering in dirty water until you have perennial diarrhea? Who volunteers to get shot at? Who volunteers to give up your right to free speech and free association? To live where and how you want? To willfully place yourself at the whim of a rigidly hierarchical bureaucracy?

But ask yourself this: Who volunteers to labor in obscurity for years with only the slimmest chance of success? Who gives up their nights and weekends, dates and parties, for what amounts to a second job that doesn’t pay a dime? Who tolerates humiliation, rejection and desperate loneliness?

Why the hell would anybody ever do that? Because it’s worth it, of course. When you’re standing at attention in your finest at a change of command, when someone shakes your hand on the subway and thanks you for your service, when you look in the eyes of a person and know they’re alive because of you, it’s worth everything you went through and more.

The same is true of writing. When you see your name in print, when someone reacts to your writing in a way you’d never expected, tells you it influenced them, changed them, transported them, inspired them, it’s well worth it.

But that part is fleeting. It’s the misery that endures. I know writers who’ve published a half dozen novels only to be dropped for mid-range sales. Others, despite dazzling popularity, couldn’t make enough to keep a roof over their heads. I’ve seen commitment to the discipline wreck friendships, marriages, minds. There are dazzling moments, to be sure, as clear and glorious as when the battalion CO pins the commendation on your chest in front of your whole family.

But it’s as brief and fleeting as that, and before you know it, it’s back to the mud and the screaming and the hard calls with no time to think it through. You have to love that mud. It has to define you. You have to be proud to be covered in it. You have to want it bad enough that you can override your desire to seek comfort. When there’s work to be done, you don’t call your friends to go out to drink and bitch. Instead, you sit down and work.

Because if it ain’t rainin’, you ain’t trainin’, and you love that mud. Because you’re a damned marine.

Oorah.

My point is this. Uncomfortable? Miserable? Wondering why you bother?

Glad to hear it.

Because you’re exactly where you need to be. The fire that’s burning you is the crucible where the iron is forged. I can’t promise you that it’ll hold up under the repeated blows waiting for it when it emerges, but there’s only one way to find out.

This is the chief reason I have avoided writing groups and online workshops. There’s a lot of great advice to be had in them, but the temptation to use them as group therapy is strong. In my floundering days, I spent a lot of time seeking ways to comfort myself in the face of the seeming impossibility of writing success. Instead of using fellow writers as sounding boards for questions of craft, I leaned on them to share dreams and pains, to know that I wasn’t alone in my loneliness and fear of failure.

And that’s not going to get you where you need to go. Work will. You relieve the discomfort (usually at the expense of work) and you take yourself out of the zone where your best work is performed and spend precious time that could be dedicated to honing your craft.

Remember Pressfield’s point. This is war. It’s not supposed to be a picnic.

This post originally appeared on John Mierau’s blog, here.

Myke Cole is the author of the military fantasy Shadow Ops series. The first novel, Control Point, is coming from Ace in February 2012.

“But ask yourself this: Who volunteers to labor in obscurity for years

with only the slimmest chance of success? Who gives up their nights and

weekends, dates and parties, for what amounts to a second job that

doesn’t pay a dime? Who tolerates humiliation, rejection and desperate

loneliness?”

Parents? Teachers? Nurses? Firefighters? Farmers?

What if you don’t want to kill people? :P

“I’ve go soul but I’m not a soldier.”

One reason why writers should not join the military:

You can get blowed up in one of our more unsavory military adventures. Dead writers can’t write.

US Army 95-2000

What a bunch of narrow-minded, self-aggrandising bollocks.

It’s the 10,000 hours thing again. You’re either in or your out. And sometimes you need a punch in the mouth to remind you (like this piece). Shake it off and get back to work.

Great piece!! Very inspiring…

Also, the headline writer should perhaps be informed that there are people in the world who are not American, and are thus ineligible to join the US Army.

>Parents? Teachers? Nurses? Firefighters? Farmers?

Parents? That’s almost everybody.

Teachers? Plenty of time off.

Nurses? Firefighters? Paid very well. Good time off. Great benefits.

Farmers? Not on the go year-round.

And all of the above can quit if they don’t like it. Well, not parents, but the paid jobs.

There are different varieties of military, and a big difference in being deployed and staying in the US (or wherever the home country is- not that many others forward deploy).

I do wonder if Mr. Cole is still in. I did my 6 and might use a VA home loan guarantee, but that’s about it.

I’m — sad? embarassed? — that people seem to be poking fun at soldiers in the comments. I thought Myke’s thoughts on self-discipline and sacrifice were really insightful. Does everyone else have no experience with military personel? I’m the stay-at-home mom of little kids, and those in or married to the military are one of the few groups that, in my experience, doesn’t instantly treat me like a waste of brain space because of it. They get sacrifice and putting something else — whether that’s country or family — above yourself. Yes, you can learn self-discipline in other ways, but I think the military really has it in spades, and I’d think that people would be happy to get some of that insight.

Anyway, I’m looking forward to Part II of this post!

Iain_Coleman, I think you should consider the following sentence:

“We’re all different. We all come at our goals from different angles. I

can’t promise that what’s worked for me will work for anyone else.”

I took that from the “narrow-minded, self-aggrandising bollocks” above.

I take it you’re not a fan of the United States military. That’s cool, neither am I. But Myke Cole isn’t the one being narrow minded here. That’d be the guy throwing personal attacks at a former soldier for suggesting that joining the military might be good for some people.

Also, this may shock you, but the USA is not the only country with an army. Those outside the US who might wish to follow his advice are no doubt free (and, in some cases, required), to try enlisting with their own national militaries. Obviously, Myke was talking about the US Army because it’s the one he has experience with.

Meh. Get pregnant.

Andrew,

Oh, give it a rest. Every profession has people in it who think that their job makes theme some kind of bloody elite. I’ve heard it from journalists, I’ve heard it from campaigners, I’ve heard it from scientists, and I’ve heard it from soldiers. It is, in every case, utter bollocks.

And of course I am perfectly bloody well aware that other countries have armies. The point, which I would have thought far too obvious to need pointing out, is that the headline is yet another example of the reflexive US-centrism that one encounters all over the internet and that grows increasingly tedious.

Hello, Iain Coleman.

It’s okay to disagree with the author of the article, but I’d prefer that you explain your disagreements, and accept that Myke Cole is sincere about what he’s saying.

Do you mean to tell me that the US-based website of a US-based publisher with a mainly US-based audience is writing from a primarily American perspective? Scandal!

Yes, Iain, every profession has those people in it. You, apparently, think everyone who speaks positively of being in the military is one of those people. I can’t see any other reason for your reaction, since at no point did Myke exhibit any self-aggrandising behaviour, or speak disparagingly of other people’s careers. Once again, you are only demonstrating the narrowness of your mind.

While I’m sure Torm.com welcomes its international audience, it is an American site run by an American publisher and almost all its bloggers are American. Complaining about American bias is just silly–adapt what you see to your own circumstances and be happy. I wouldn’t go to orbit.co.uk and complain about its insensitivity to its non-British audience.

Hello, Iain Coleman. Could you please show a little more respect for the local discourse? Myke Cole is not unthoughtful. It would have been enough to point out that he’s being U.S.-centric.

Many people think there’s some elite aspect to their profession. That’s normal, and I don’t think it’s inappropriate. People who work in a specialized field do tend to develop specific skills and talents to a level not found in the general population. Their belief that those skills and talents are valuable may be what got them into that profession in the first place.

In any event, I don’t see your grounds for dismissing it as “utter bollocks.” Are you saying it’s impossible that any profession could require or attract people with greater abilities than any other?

This was an extremely thought-provoking article, Myke. Thank you for writing it.

I can see how joining the military can help you write military SF. But there are lots of other things to write about, too. They say you should write what you know, and often young writers are encouraged to go out an experience life before they write about it. And as folks have said above, there are a lot of ways to learn how to be miserable besides joining the military.

Although, I also know a lot of people whose lives have been improved by their military service. I certainly think I am a better person for having served. Now, if only Tor would fish my first novel out of their slushpile and give me a call… ;-)

Just to point out Marine is capatailized. It is a proper noun.

Not always, Tarin.

For example:

The marines trashed the bar.

The Marines trashed the bar.

The first sentence describes the action of some individuals. The second describes a deliberate act of the Corps.

Myke, all I can say is, “Amen!” It took me a lot of years to claw up to pro level too, and in many ways, the clawing never stops. You get to the top of the hill, only to see a mountain revealed before you. There is no such thing as “made it,” though there are moments when — having extended yourself beyond the envelope — you can reflect and find satisfaction. Much as in the military, to be sure.

My own military experience informs my writing in many ways — which I covered in the guest blog at your site, and thank you again for giving me a chance to contribute in that regard. But it has also taught me (as it’s obviously taught you) the hard wisdom of suffering, self denial, long, protracted effort, and the stubbornness that comes from realizing the road march is what it is: those 15 km won’t evaporate by themselves, it’s all about putting one boot in front of the other and ignoring how much your feet hurt.

Kudos to you on the new book, the new series, and for this very insightful article. I am totally linking to it.

I’ve been thinking about this article since I read it, yesterday, and on consideration, I believe I disagree with it on a visceral level.

Leaving aside for the moment Mr. Sykes’ contention that one must have experienced misery, physical or otherwise, to be a better writer, and the fact that there are any number of people whose work takes them into similar miseries (let’s take humanitarian aid workers as an example) –

The American exceptionalism on display here disturbs me. That, and the disappearing of the perspectives of the people on the other end of the gun. I don’t doubt Mr. Sykes’ sincerity in his belief that his military experience made him a better person/writer. But I do think there’s something dubious about advocating “become a better writer” as a primary reason to join an organisation whose function is the elimination of his nation’s enemies, and whose record with “collateral damage” is… well, speaking as a non-American, rather unpleasant.

It’s not that I think there’s no good reason to join a military (the only reason I’m not part of my own country’s reserves is because they refused me on medical grounds), but I do think this article is more than slightly dismissive of all the reasons why someone would or could not.

Also, group therapy saves lives. Don’t knock it, please.

This could also be why every writer should get themselves incarcerated, or pregnant, as another commenter suggested. Homeless and unemployed would so totally work as well; try concentrating on writing while you’re freezing your ass off as your body devours itself. Easy, see? Your misery will be a font of sublime inspiration. Get published and it’ll be a real heart-warming story of rags to r–err… well you might not freeze to death next winter.

I’m sorry, but this is some of the most condescending nonsense I’ve ever read here. You look people in the eyes and believe that they’re alive because the U.S. military is causing terror in other countries? Give me a break. I can only hope I’m misunderstanding what I’m reading (which is entirely likely considering that I skimmed most of it).

*facepalm*

I mean “Mr. Cole.” (What is it with me and names lately? Damnit, brain.)

Oh would you all quit whining about the article. It was a thought provoking provocative piece written by a talented writer who wanted to share what worked for him. He prefaced with the comment that it wouldn’t work for everyone.

If you agree, it’s a cool article. If you disagree and get angry about it, then you’re precisely the narrow minded person you claim to be railing against. If you disagree and are able to sit back and say ‘huh, I disagree but that’s cool. Guy who served his country (and continues to do so) who made his dream come true, props to him’ then I tip my hat to you.

Myke, awesome post. Looking forward to the book.

@karin – the homeless & unemployed bit worked well for George Orwell.

Kudos to you Myke for sharing your experience here, and many thanks to you for your service to our country. I feel this is a well written piece, a man’s experiences and what helped him become a better writer. Myke was sure to indicate that this worked for him, and that everyone else is different. He did not denigrate anyone else or their path to the same goal. I wish the same could have been said about some of the commenters to this thread. I look forward to reading Myke’s book when it is published.

I’ve met Myke and like him fine, and I thought the essay was interesting. However, the headline should have been edited to actually suit the content. It’s clearly not about why every writer should join the US military (gee, even members of al-Qaeda?)—it’s about what Myke feels he got out of his military experience. The theme of misery as a unique crucible also should have been altered; it’s a personal one. Plenty of people get out of the military and retire to their couches with a bag of chips like anyone else. Others are shaken terribly and simply can’t get their lives together afterwards. After all, the military cycles through hundreds of thousands of people. One size never fits all.

I had the privilege of editing two books by Stan Goff (82nd Airborne, Army Ranger, now a socialist activist) and he was a very disciplined guy—partially thanks to his military experience, and largely thanks to his post-military political experience. And if he wrote an essay entitled, “Why Every Coastie and Reservist Puke Who Wants to Be a Writer Should Join The Communist Party Instead” when the topic was really his own experiences doing the same, I would have altered the title. Then there are excellent writer-veterans such as Larry Heinemann. If anyone out there would like to be punched in the face by a great novelist, find Mr. Heinemann and thank him for his service in Vietnam. If the label on the tin says “This Is For Everyone!” and the contents ain’t, then change the label.

PS: anyone who thinks farmers aren’t on the go year-round should visit a farm.

Some of us, for sundry medical reasons, would be rejected by the military. I can see what you’re getting at, and why it might have made the difference for you.

But “Every Writer”?

If you’re looking for sustained misery, the way the politicians are talking, it’s not going to be monopolised by the military.

Yes, it worked for you. Great. But part of the success of a military can be attributed to the way it re-works a soldier’s mind, Maybe that is why, in so much fiction by ex-soldiers, I see the same habits, the same assumptions about people. And when I see “Every Writer”, maybe words chosen for you, I am inclined to doubt that you will be any different.

Sooner or later, it gets boring. Be careful how you fulfil that contract.

I appreciate (as a career soldier) the underlying sentiment, but I think it’s a bit narrow. I don’t know that misery, qua misery, is needful. Focus is, sure, but there are lots of ways to get focus, and the miseries of being in service are different to those of being homeless, or cripled.

The fundamental difference is that one who enlists voluntarily, has accepted the miseries. Those miseries are also related to the service, they aren’t immutable, and they aren’t permanent (ignoring service related disabilities; which isn’t what Mike is talking about).

Nixon said, “Until one has been a part of something larger than oneself, one has not truly lived”. He was talking, I think, about his time in the Navy, in WW2.

I think, in some ways, he is right; and I think that the sense of something larger than oneself, which one can identify with, is part of what makes a good writer. Tapping into things others can identify with is what makes a story gripping. Misery can be a shortcut to that (it can also be a long hard road), but I don’t think it’s the only one.

And, for all that I enjoyed (much) of my 16 years, I know, straight up, that it’s not for everyone; it wouldn’t have been for me, if I’d been 18, instead of 25 when I enlisted.

@Mark_Lawrence:George Orwell was also a policeman and fought in the Spanish Civil War, where he got shot through the throat and almost died.

Would that be considered necessary misery, too?

Maybe not @36, Orwell deliberately experienced various kinds of down-and-out misery. I’m not sure that would be the right thing for every writer, but I think Orwell judged correctly that doing it was good for him.

@@@@@ Karin #25: Maybe I misunderstood, but I thought the writer was talking about a very specific person… like a military buddy…whose life he had saved through his own sacrifice in harm’s way NOT everyone in general.

Anyone feel free to correct me if I misread.

As a huge fan of all Steven Pressfield’s work, and an author myself, I can absolutely appreciate the sentiment Pressfield alludes to, and that Myke Cole takes deeper here.

It lacks weight on the surface -in international terms – because most other Western nations and cultures lack the same fierce, uh, ‘regard’ for their own militaries that the US embodies so patently; to many others, it’s uncomfortable (to put it politely) and joining the army isn’t a de facto means of bettering yourself or objectively doing valuable service. If the last 15 years of war have proven anything in the age of globalised instant media, it’s that nations can take up arms for the most unpopular and spurious reasons, and very few countries outside the States laud its soldiers time and again for fighting in those conflicts. Just being a soldier isn’t necessarily worthy of pride to a lot of people, especially given the nature of the wars they fight.

So the sentiment of endorsing suffering (and the trials of a difficult real life adding flavour and perspective to writing) are a great slice of advice, but as several people have pointed out, there’s a much broader perspective to be gained. That level of companionship, brotherhood, suffering and endurance can come in other ways, in other flavours, and are as valuable and worthy as many other perspectives.

Sounds a lot like graduate school to me. There are probably many places to have this sort of experience.

It does feel like there’s an elephant in the room, raised (nervously?) by @3. In that… there are a lot of professions/careers/life paths/choices/destinies/routes to ‘productive misery’, but not all of them involve the legitimate expectation of being put in a position where you have to end other people’s lives.

I have the utmost respect for the military and understand that 99% of the time, its role has nothing to do with engaging in or supporting combat. But – unless I’m missing something in my read through of Cole’s article – that should probably be mentioned as a fairly major consideration.

On a broader note, I don’t entirely agree with the premise. As Nick says @33, this may be down to the misleading headline. But writers write. There are plenty – perhaps the vast majority – that have managed without throwing themselves into deep misery. I think there are multiple paths to developing the creativity/rigour/empathy/whatever that someone needs. And, to be honest, I’ve always found something slightly off-putting and self-aggrandising about the very notion of having to ‘suffer for one’s art’. Writing a book is already an impressive achievement, further initiations aren’t necessary.

A headline is just that, a headline. Clickbait used to generate interest. Nothing to get worked up over. He did preface his comments by saying that this path doesn’t work for everyone. That being said, it has indeed worked for many writers, even if they did not get quite the same things from their experience as Mr Cole did. Robert Jordan, John Ringo, David Weber, I’m positive that there are many more who have served and had that experience inform their prose. And of course there are other professions that will do the trick. I really don’t think he was trying to be dismissive of other people’s path to the pros.

I think some people have a visceral reaction against the military in general. I don’t believe if he said “you should be a teacher if you want to write novels” that the reaction against the article would have been as strong. That he is biased toward the military is obvious; he sees parallels between his service and his budding career. He therefore writes what he knows. It would have come off as insincere if he tried to speak on a career path he never had.